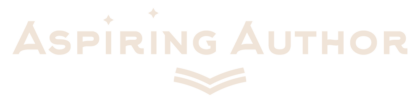

Author Shannon Bowring is special. Not only is she a contributing editor to Aspiring Author, she has also been a fierce champion and brilliant friend, nestling into my corner from the get-go. She accepted and published one of my weirdo short stories when she was Editor-in-Chief at the Stonecoast Review, for which I will be forever grateful. Along with fellow contributing editor, Darcie Abbene, we have been in the trenches of submitting work–both short- and book-length–as well as securing literary representation and book deals. We have spent multiple hours researching the business of publishing, talking with other writers and industry professionals, and honing our submission materials. During this time, we have leaned heavily on each other, cross-referencing information, sharing experiences, and reflecting on the lessons we have learned along the way. And most importantly, never giving up in our pursuit of our author careers. Shannon is a boss, a queen, and I couldn’t be more elated to publish this interview just as her stunning debut novel, The Road to Dalton, explodes into the world. I’m not crying; we’re all crying.

How did you get into writing?

To begin with the beginning: I was born with two congenital heart defects that kept me in and out of hospitals for the first several years of my life. Books were my best distractions from that trauma, as well as from the boredom that comes with living in a working-class town of 1,300 people in the northernmost county of Maine. I loved that I could read a story and be taken to an entirely new world. It wasn’t much of a stretch to want to create my own new worlds by writing my own stories. As I grew older, though, my writing tended to focus on the world I knew best: my hometown, which became Dalton in my stories. So I’ve essentially been writing my debut novel, The Road to Dalton, my entire life, memorizing the field-and-forest topography of Aroostook County, absorbing the language and culture, considering the secrets small-town people keep (or try to keep). More than that, and beyond Dalton, writing has been one of my constants throughout my life, the thing I turn to whether I’m happy or depressed, the thing I never get bored with or lose passion for. Writing has often saved me from the PTSD I still deal with from all my years of hospitals and heart surgeries. I also genuinely believe it’s what I was put on this earth to do.

How important is place in your writing?

It’s more than important—it is intrinsic. Imperative. Fundamental. While I was writing The Road to Dalton, it was crucial to me that I write it in a way that revealed Dalton not only as the main influence on the characters, but as its own character. I believe people, fictional or real, are shaped by the places they were born, the unique environment that raised them. In Dalton’s case, that means my characters have an abiding appreciation and respect for the landscape of Aroostook County—rich forest, rolling fields, clean rivers, endless sky. My characters also depend on that landscape to provide their livelihoods, farming and lumber being the main industries in that region of Maine. The characters in The Road to Dalton are members of a close-knit community of people who take pride in helping one another out. But they are also part of an inherent culture that discourages open discussion about everything from sexuality to mental health—and that sort of culture can lead to devastating effects, as I tried to show in the book.

The Road to Dalton is told through multiple perspectives of characters ranging from fourteen to forty-something. Why did you choose that narrative structure?

In a tiny community like Dalton, everyone’s stories are braided together—the town doctor is married to the library director, who is best friends (or maybe something more) with the mother of the rookie cop whose wife is silently suffering from postpartum depression… Everything and everyone is related, either by blood or experience. However, even though the characters all have Dalton in common, each of them has a unique, individual experience with and relationship to the town. Multiple perspectives felt truer to a place like that, where your story is never just yours alone. I also just get bored writing only one character. As an author, and as a reader, I require variety.

The Road to Dalton began its life as a linked story collection, before evolving into a novel. Which do you prefer?

I love both! And I think often the two are interchangeable. Julia Phillips’ Disappearing Earth is designated as a novel, but it feels more like a linked collection to me. Morgan Talty’s Night of the Living Rez is an intentional linked collection that reads like a novel. I also believe too much weight is placed on those terms—story collection versus linked collection versus novel. If you enjoy the reading experience and come away feeling as if you’ve read a good book, does it really matter what genre the publishing world decides to slot it into?

Describe your publishing journey

I started submitting short stories to lit mags toward the end of college, probably 2011 or 2012. I got my first acceptance in 2015. Since then, I’ve pretty consistently had stories and essays published, and my work has placed in and/or won several contests. When I finished writing the first draft of The Road to Dalton in the fall of 2021, I began querying agents. Around that same time, one of my short stories, “Epitaphs for Almost-Strangers,” appeared in the Raleigh Review. The editors there reached out to me to say that a literary agent had read the piece and wanted to get in touch with me, to which I of course said HELL YES. That’s how Nat Sobel came into my life. He emailed me with generous feedback on the story and asked if I had any book-length projects ready to go. By then, I’d only sent out about a dozen queries, all either polite rejections or ghosts. I sent Nat The Road to Dalton, he and his team read it, and Judith Weber accepted the challenge to try to sell it to the world. She and I worked closely together on revisions for a few months, then the MS went out on submission in April 2022. About thirty passes later, in August 2022, Kent Carroll and Autumn Toennis at Europa Editions took a chance on a “quiet” debut. Some contract-signing, more revisions, a lot of behind-the-scenes magic, many, many email chains, and here we are.

Who are your literary inspirations? Mentors? Favorite books?

This question always stresses me out, because I never want to omit any writer who has had a positive impact on me. So consider this by no means an all-inclusive list: Alice Munro, Jhumpa Lahiri, Edward P. Jones, Elizabeth Strout, Marilynne Robinson, Eowyn Ivey, Lorrie Moore, Joyce Carol Oates, Leigh Newman, and Morgan Talty. And all my Stonecoast MFA mentors: Aaron Hamburger, Ron Currie, Jr., and Susan Conley. And books: Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio; Elizabeth Strout’s Olive Kitteridge; Julia Phillips’ Disappearing Earth; Eowyn Ivey’s The Snow Child; Daniel Woodrell’s Winter’s Bone.

I’ve heard you defend quiet books. Talk to me about that…

I think the definition of a quiet book is a bit different for everyone, and it tends to go hand-in-hand with literary fiction, which is also a bit of an intangible term. Quiet, for me, means: A story driven by character rather than plot. A narrative that pays close attention to language—the rhythm of words in each sentence, vivid imagery, quite a bit of metaphor. Quiet books often revolve around place, particularly rural or wild settings. Rather than shocking the reader with crazy twists and turns, a quiet book subtly leads the reader along the same meandering paths its characters take. But quiet doesn’t mean there’s no room for surprise or mystery or suspense, and it definitely doesn’t mean nothing happens. It just means the reader might have to pay a little more attention to all the things happening both on the page and off. I like that kind of subtlety. On the complete opposite end of the spectrum, I also love true crime books about the most heinous murders and depravities you could imagine. Nothing quiet about that genre at all.

You’ve been Editor-in-Chief at the Stonecoast Review and a contributing editor to Aspiring Author (yay). How has editing helped you hone your craft?

It’s impossible for me to separate editing and craft. I’m not one of those writers who dread revising my own work—I love it. I love the magic in reworking a sentence until it’s just right. I love fact-checking to make sure the Whitney Houston song my characters are listening to came out in the correct time period. I love trimming dialogue back and back and back until I’m left with the realest thing a character would say, in their truest voice. I edit as I go, so I don’t always get the page numbers or word counts I’d like to see. But I can’t just plow ahead knowing I’ve left a mess behind. That could be the mark of a natural editor. Or of someone with anxiety and OCD. Or maybe those things are the same thing.

What books on writing and/or publishing do you recommend?

Stephen King’s On Writing.

Anne Lamott’s Bird by Bird.

Ray Bradbury’s Zen in the Art of Writing.

George Saunders’ A Swim in a Pond in the Rain.

How do you separate the business end of writing from the craft?

If I’m writing a chapter or story, I try not to let myself answer emails from my editor. If I’m researching publications and contests to submit to, I try not to give up on that to rework a scene I wrote earlier in the day. In other words: Compartmentalizing. Also a fair amount of procrastinating.

What is your daily writing routine?

It varies. On weekdays, I try to fit in writing time wherever possible. Weekday afternoons are usually when I catch up with the tedious but necessary administrative parts of being an author—answering emails, researching places to submit work, etc. Weekends are my best time to write. I like to wake early, get settled at my writing desk, and write for at least a couple hours. Then I’ll take a break to read or snack or watch a murder show (depravity!). Then I’ll spend another couple hours in the afternoon, and one or two more in the evening, writing again. I like that kind of intermittent but all-day focus; the creative in-and-outness… is that a term? I’m making it a term.

What cool things have you learned as a debut novelist?

Publishing is a business, but the amazing team at Europa has made it feel like a labor of love. I’m so grateful to be working with an indie press—my emails are always promptly replied to, my many, many questions always answered. I feel incredibly supported as a debut novelist, and I’m not sure that would have been true had the book been picked up by a Big Five publisher. I also don’t think a big house could have given Dalton or its characters the same attention, enthusiasm, and devotion that my editor, Autumn Toennis, has given them from the moment she read the book. She’s been a wonder to work with, and I’m so happy to have her in my corner. Another cool thing is observing how genuinely excited people are to hear about the book. Not just the people you’d expect—friends, family, fellow writers—but random folks like my dental hygienist or the cashier at my local grocery store. It’s been really heartening to see so many people appreciating books and the authors who write them.

You’ve won competitions for your short fiction and received a Kirkus starred review for The Road to Dalton. How important are these accolades in helping launch a debut author’s career?

I would say it’s an ugly truth that more people tend to take more note of authors who have received some kind of accolades. Having that added exposure as a debut author is obviously a great boost, because it’s a lot of work to get your name out there and have your work recognized and taken seriously. Another ugly truth is that I’m just as thrilled to receive an honor or favorable review as the next person. But I think what’s most important is that I, or any author, never stop being grateful, and we never let any prize won or lost distract or deter us from the work of writing. Because that’s the most essential part of this literary life—the writing itself.

We completed our MFA together. Would you recommend the MFA to aspiring authors?

For me, personally, it was the right decision to go for my MFA. I had about a decade after college where I was writing short stories and getting them published on a semi-regular basis. I won or placed in a few small literary contests. But I eventually hit a creative and professional wall—I wasn’t part of a writing community, my work was getting stagnant, and I was feeling discouraged about any literary career prospects. Stonecoast reignited my love of writing, exposed me to new ways of thinking, helped me recognize what I did well and what I could do better, and connected me with a massive support system of other writers. That was the biggest thing—that community. And the enforced deadlines that enabled me (sometimes forced me) to finish writing The Road to Dalton. That said, I’ll be paying off those student loans for a long time, an ever-present stress looming over me. I think MFA programs in general are evolving (hooray for shifting away from the traditional white male canon!), but they remain cost prohibitive for a lot of talented, driven writers. And MFA programs are time-consuming, energy-sapping, brain-consuming—not every aspiring author is in the position to take that time and focus away from work, family, life in general. So I would say that if an MFA isn’t possible for you, or even of interest to you, there are still lots of great ways to refine your craft: Adult ed classes, online workshops, retreats or conferences, books on writing, local writing groups. The most important things are that you read widely and voraciously, keep learning new ways to hone your craft, and connect with a community of other writers who will challenge, inspire, and encourage you.

We talk all the time, constantly supporting each other as we navigate the great publishing unknown. How important is it to find your writing people?

It is essential. And if I, a happily introverted loner, am saying that, then you know it must be true. Seriously, though, I don’t know how I could have navigated these rough waters without you or any of my other writing people. From acting as a sounding board for story ideas, to beta-reading, to being there for all the neurotic venting that comes along with the querying and publishing journey—it’s crucial that you have a support system in place.

On a similar note, how important it is to encourage and celebrate, rather than compete with, fellow writers? Have you ever experienced professional jealousy?

There will always be some jealousy when you hear someone scored a bigger book deal or prize than you—that’s just human nature. But the publishing industry is brutal enough on its own, so let’s not make it worse by being d*cks to each other. Pop the champagne, sincerely congratulate that author rolling in cash and accolades, and get back to writing your own sh*t.

What advice do you wish you’d listened to or ignored?

Build and maintain an online presence. This is one I wish I could ignore. I’m not a huge fan of social media, and posting “interesting” content doesn’t come naturally to me*. But it’s helpful for aspiring authors to have some kind of online presence, even if it’s just an author website where you can direct people to works you’ve had published. *For all advice regarding this topic, defer to our internet-savvy Editor-in-Chief, Natalie Harris-Spencer. I promise, I’m really not the one who should be helping you here. Wink emoji.

What does success look like to you?

A life built around creativity, curiosity, gratitude, and patient tenacity (to borrow a phrase from author Deb Marquart).

What keeps you sane?

My husband. My cat. Books, of course. Rivers and trees. Music. Chocolate. And writing, of course.

How important is it to you to pay it forward to aspiring authors?

So important! I wouldn’t be where I am now if I hadn’t had other authors who were kind enough and knowledgeable enough to help me along the way. I’d be so happy if I knew I’d helped even one writer have the courage to hit that big scary Submit button.

What advice would you give to aspiring authors looking to get published?

You will never get published if you never hit that big scary Submit button.

About Author Shannon Bowring

Shannon Bowring has been nominated for a Pushcart and a Best of the Net, and was selected for Best Small Fictions 2021. She holds an MFA from the University of Southern Maine’s Stonecoast low MFA residency program and currently resides in Bath, Maine. The Road to Dalton is her first novel.

Recommended reading

Here at Aspiring Author, we love recommending bestsellers and fawning over hot new releases. On this real time recommended reading list, you will find a list of top rated books on the publishing industry, craft, and other books to help you elevate your writing career.